Producers strive to replenish reserves amid soaring demand

This article was written by Kate Allen and was published in the Toronto Star on March 25, 2024.

Throughout what should have been the frigid depths of winter, an unseasonably warm sun beat down on a series of billboards and bus-stop ads across Toronto. The campaign urged passersby to consume even more of a familiar, maybe even patriotic, household staple: maple syrup.

“It’s not just for breakfast,” the ads propose.

The implicit assumption of the billboards, and of pancake eaters nationwide, is that maple syrup will always be available for breakfast. But a collision of forces have brought the billion-plus-dollar industry to an uncertain moment.

Built to hold 133 million pounds of syrup, Quebec’s reserve has dwindled to just 6.9 million pounds, a fraction of where it sat just four years ago

Quebec’s strategic reserve of maple syrup, a trio of vast warehouses that typically hold tens of thousands of barrels, is nearing empty after a couple of warm winters collided with a pandemic-era spike in demand. Built to hold 133 million pounds of syrup, the reserve has dwindled to just 6.9 million pounds, a fraction of where it sat just four years ago.

Now, as the sugaring season runs on after a balmy winter-that-wasn’t shattered historical records, producers are eyeing taps with concern.

“We really, really need a good production year this year, because we want to not only fill the markets with the product that it needs, but also be able to build back the strategic reserve,” said Simon DoréOuellet, deputy general manager of Québec Maple Syrup Producers.

Doré-Ouellet said there is no concern of an immediate shortage, and his organization is distributing millions of new taps across the province in an effort to ramp up production over the coming years. Quebec provides roughly 90 per cent of the maple syrup tapped in Canada, and more than two-thirds globally.

But the reserve, the only one like it in the world, exists in part to stabilize supply — and prices — in Canada and beyond. It has also provided the foundation to push Canadian maple syrup into new global markets as distant as Australia and Japan.

“You can go into any Metro or Food Basics or Loblaws or whatever, and you could find maple syrup at a price that’s fairly predictable. Well, it might be a lot less predictable if we start to get to the end of the reserve,” said Warren Mabee, director of the Queen’s Institute for Energy and Environmental Policy and an expert on forestry and forest products.

“One of the worst things that could happen would be to have a shortage of product, given how much we’re trying to push maple syrup and export it worldwide. So it’s really important for us to be able to count on that strategic reserve,” said Doré-Ouellet.

In some ways the current stresses are a signpost of success. Maple syrup consumption has spiked in recent years, seemingly driven by sticky pandemic habits.

Syrup sales were rising at respectable, single-digit percentages annually prior to 2020. Then COVID-19 hit, restaurants closed and people started cooking at home. From 2020 onwards, sales spiked up to 20 per cent annually, and have stayed high.

The Quebec federation has also been heavily promoting Canadian maple syrup, both at home and abroad. The Toronto billboards are their work: Ontario’s vastly smaller industry only produces about half the maple syrup consumed in this province, with Quebec backstopping the rest. In Canada’s biggest export market, the U.S., the industry group is battling the twin foes of corn syrup and table syrup. And overseas, the group has been promoting Canadian maple syrup in countries like the U.K., Germany, Japan and, for the last year and a half, Australia. “There’s a lot of interest around brunch in Australia, so that’s great for maple,” DoréOuellet said.

The strategic reserve has been critical to these forays, he adds.

Winters, however, have not been co-operating with these ambitions.

Ideal tapping conditions rely on a delicate dance of temperatures. Cold nights below zero force sap up the tree, while warm sunny days see the sap flow back down. As it flows, it can be tapped, boiled and turned into syrup. Without the cold-warm night-day cha-cha, sap can be harder to draw out. Once the weather stays warm for too long, the tree uses the sap as energy to bud, throwing off its flavour and ending the sugaring season.

In 2021, as syrup’s popularity was booming, a warm winter cut the season short. Canada’s yield that year was down 21 per cent compared to the year prior. The Québec Maple Syrup Producers tapped the strategic reserve to meet the crush of demand, releasing 50 million pounds — about half the stores.

The next season, 2022, saw record-breaking yields. But the bonanza was just enough to satisfy the existing market, Doré-Ouellet said, with nothing left over to replenish the reserve.

Last year’s mild winter ushered in another short season. Since then the reserve has been drawn down to its current level, the lowest since 2008, according to Doré-Ouellet. (The strategic reserve has existed since 2000, capitalizing on pasteurized syrup’s ability to sit without spoiling: some was recently released that had been stored since 2011.)

“We’re hopeful that the season is going to be a really successful one. And we really need that,” said Doré-Ouellet.

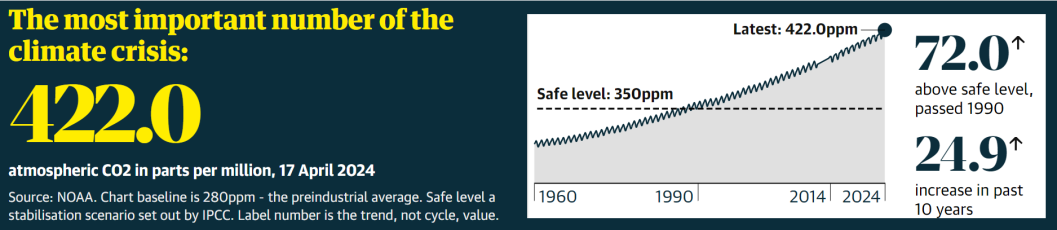

This past winter was the warmest in Environment Canada’s more than 75 years of record-keeping: seemingly not a great omen for the sugaring season. It also raises the question of whether climate change is colluding with natural variability to scramble syrup production. Neither of those questions is easy to answer at this point for this particular year.

Bill Vandenberg, who helps run Ryan’s Sweet Maple with his son Ryan Vandenberg in Lambton Shores, said the family operation’s first boil was on Feb. 1 — “almost a week earlier than last year, two weeks earlier than the year before, and three weeks earlier than three years ago,” Vandenberg said. By the first week of March, their season was done.

Even though the season started and ended very early, Vandenberg said they eked out a decent yield: about 1.67 litres per tree, compared to two litres on average. Part of their success was that they had been following reports of the mild winter all season, and were ready to tap by late January. But all the syrup they produced will likely go straight to the consumer market, with nothing left over to sell to bulk suppliers.

John Williams, the executive director of the Ontario Maple Syrup Producers’ Association, said the Vandenbergs’ story is representative of what he’s hearing across the province, which typically acts as a canary for Quebec’s slightly later, much larger season: those who were ready to go early got a decent run.

While Williams said that there have always been wacky winters once in a while, the increasing frequency of mild seasons, and decreasing frequency of ideal daynight conditions, is prompting producers to not only change their mindset but also upgrade their technology. While most sugaring operations used to rely on buckets and spiles, more are upgrading to vacuum tubing systems able to suck more sap from the tree over longer periods. The sugar shack, meanwhile, has become less of a shack and likelier to be full of gleaming gear like reverse osmosis units, which remove water from the sap and speed up the evaporation stage.

While many producers do recognize the role and risks of climate change, “I don’t think for the most part anyone’s panicking,” Williams said.

Producers are adapting, and since Ontario is on the northern edge of the maple trees’ range, he said, “hopefully we can mitigate things in the meantime … control our emissions, and stop it from getting too far out of whack.”